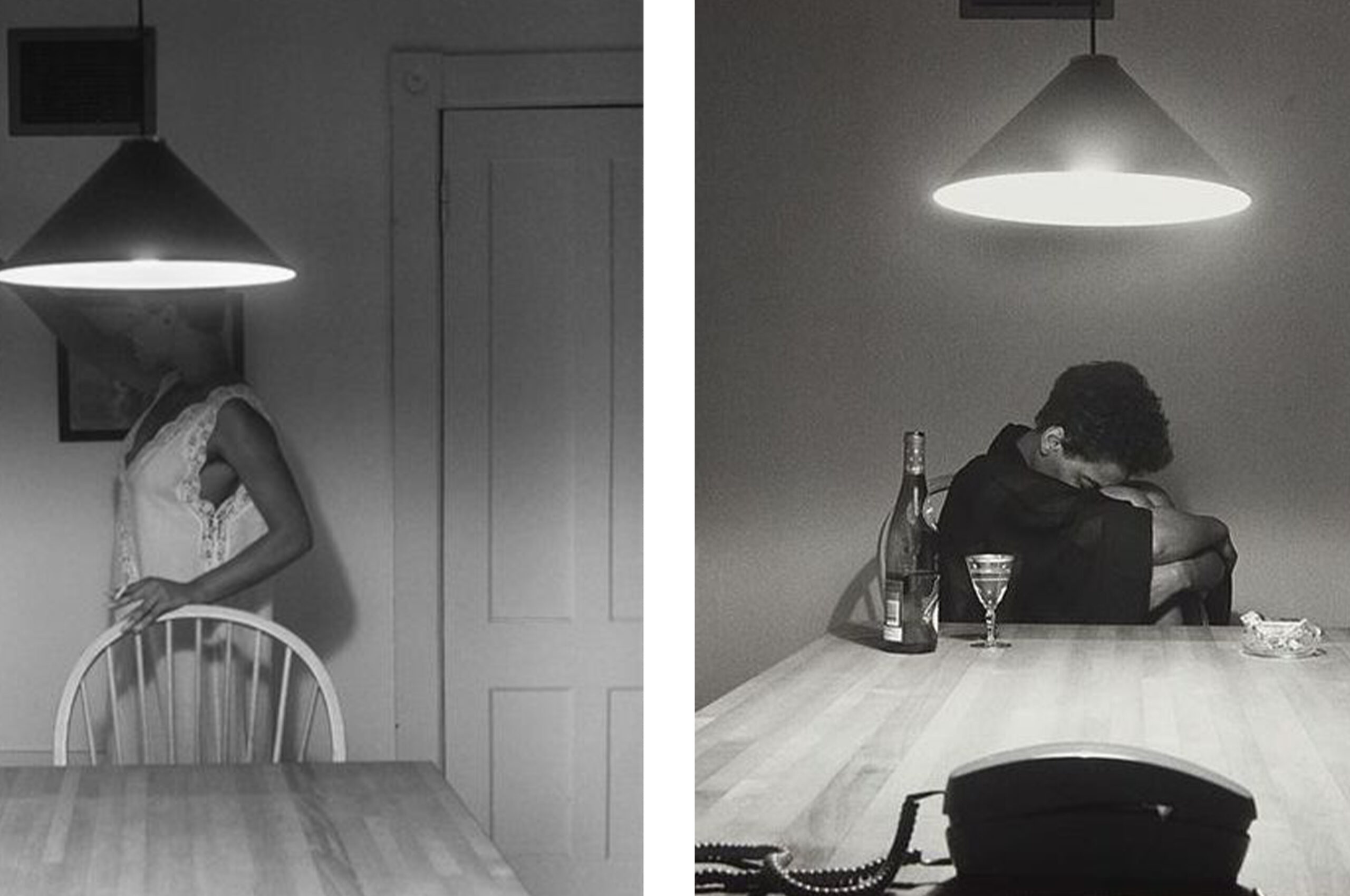

Reclaiming the Healing Power of SLEEP

A reflection on shifting our societal approach to sleep and rest.

By Elvira Vedelago

A reflection on shifting our societal approach to sleep and rest.

By Elvira Vedelago

Late last summer, somewhere between our first lockdown in the UK and the following roulette of ever-changing tiers, I met a friend for a coffee and overdue catchup. After updating one another on ‘new normals’ and managing life in a pandemic, we talked health and she confessed to feeling like something might be wrong with her brain. She complained of increased headaches, difficulty concentrating, tired eyes and general fatigue. She had yet to see her doctor, but I wondered what else was happening for her that might have prompted the development of these symptoms. Was she using her laptop more intensely? Did she need glasses perhaps? Was she stressed? For her, the only noticeable change was around work: her workload had increased quite dramatically and as such, she was averaging four to five hours of sleep a night, with an occasional afternoon nap to help. While I encouraged her to seek medical advice to be sure of what was going on, I was surprised that she didn’t initially see the potential connection of her symptoms to the amount of sleep she was getting; she didn’t register how sacrificing a few hours of sleep a night could have serious long-term consequences beyond feeling a bit tired. Perhaps more worrying was that she had resigned to the fact that cutting into her sleep was a necessary trade-off to hit and maintain her desired targets.

I’ve been thinking a lot about that interaction since and reflecting not only on my own relationship with sleep but also society’s understanding of rest. I’ve noticed a growing pattern amongst several of my friends and family who complain about burnout and ill health but brush off the suggestion that what they really need is meaningful rest. “I don’t have the time” or “I’ll sleep when I’m dead” is usually the response. A colleague once told me he felt so tired that he could “sleep for 100 years.” Yet dismissed any advice on prioritising sleep. I wonder where along our history we have been duped to see rest as for the weak. And why we believe that sacrificing our physical and mental health for the glorification of ‘the grind’ will end with happiness when the word itself speaks of reducing something down to its smallest particle, to crushing it? As the borders between starting and stopping work in industrialised nations become increasingly blurred for many, eating away at the time available for rest, we are slowly collapsing under the weight of said grind. A 2018 poll found that the average Briton gets just over 6 hours of sleep a night, naming busy lives and hectic work schedules as the main cause, and the World Health Organisation has warned about a growing ‘global epidemic of sleeplessness’. To develop more of a positive relationship with sleep (as a previous insomniac), I resolved to start this new year by better educating myself on the significance of sleep, the severe impact of sleep loss and why our societal approach to sleep needs to change.

The damaging impact of sleep deprivation on daily life is no longer news. Countless research, reports and articles remind us that the cumulative long-term effects of sleep loss have been associated with a wide range of negative health outcomes, including an increased risk of Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, obesity and depression. In fact, most major diseases in the developed world have strong causal links to inadequate sleep. Simply put, the less you sleep, the shorter your life expectancy. Worryingly, even one night of poor sleep can have a significant impact on your immune system, weakening the body’s defences against infection and disease dramatically. While most people understand sleep as a basic need, cultural attitudes to work, play and rest still force us to cut corners on sleep, irrespective of the fact that doing so has a clear impact on health, mood regulation, safety and productivity.

Yet the odds aren’t stacked evenly and as a woman of colour, I often worry about what space is available for us to rest. A talk given by Dr Gabor Maté on the relationship between stress and disease, which I attended in London two years ago, highlighted that over the last 100 years or so, women’s health has been steadily deteriorating, in part as a result of our increased workloads, the emotional burdens we carry for ourselves and our communities and the gendered/racial discrimination prevalent in the societies we live in. Since that talk, I keep thinking about how the interactions between gendered role expectations and a history rooted in systemic oppression might leave women of colour little room for sufficient rest. Socioeconomic factors and historical stigmatisation determine who is afforded the privilege of rest in our society, yet the distinct inequalities that exist across different ethnicities are somewhat ignored in public health conversations.

“I keep thinking about how the interactions between gendered role expectations and a history rooted in systemic oppression might leave women of colour little room for sufficient rest.”

Psychological stressors such as racial discrimination, immigration status and economic hardship impact sleep quality, making it more difficult to fall or stay asleep. Reports have found that people of colour are getting much less sleep than their white counterparts and, in particular, black people in Western nations, such as the UK and US, struggle more with disorders like insomnia and sleep apnea, leaving them susceptible to the development of high blood pressure and heart disease. Inequalities are also found across the sexes, where women are 40% more likely to have insomnia than men and suffer disrupted sleep as a result of an unbalanced division of social responsibilities and unpaid labour. Although I haven’t come across any research as of yet, I dread thinking about the stats for black women, in particular, who have to navigate the intersection between white supremacy and patriarchy, upholding the ‘superwoman’ narrative and calls of self-sacrificing for the benefit of the collective. Naturally, all these issues have been exacerbated by the pressures of the present coronavirus pandemic.

Although there has been a boom of media coverage on the subject, the commercialisation of self-care by the wellness sector and the birth of a multimillion-dollar sleep industry only offer quick-fix solutions to plaster over a much deeper issue, when what we really need is a radical shift in our personal, professional and societal appreciation of sleep. Our current sleep epidemic, and resulting public health crisis, shows us that we must move away from what has become a really violent, capitalist framework—that which values production over the primal need to rest—and instead lean into the natural cycles that the body has perfected over thousands of years of evolution. A cultural reset in how we approach sleep is necessary, perhaps even reverting to the patterns of our ancestors whose body cycles were better attuned to the planet’s daily rhythms. A 2015 study, attempting to understand how humans slept pre-modern era, examined the sleep patterns of three current preindustrial societies (those without modern schedules or Netflix accounts) and found the following: sleep periods averaged 6.9-8.5 hours in summer (and about an hour longer during winter), with the onset of sleep occurring approximately 3 hours after sunset and largely dictated by the daily cycle of temperature change. Extensive health studies of these hunter-gatherer tribes have found that although the rates of child mortality are higher in these communities than in “modern” civilisation, they reported better physical health than industrial populations. While our technologically advanced society would have us believe that we are better off than our ancestors, there are clearly important lessons to be learned from our past, particularly when looking for sustainable solutions to the modern world’s sleep problems.

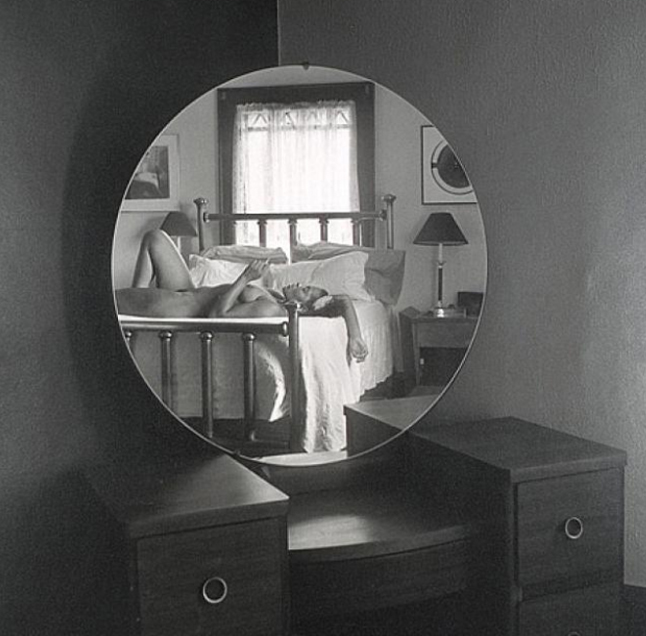

Reading Matthew Walker’s seminal book Why We Sleep: The New Science of Sleep and Dreams at the start of this year, I began to appreciate the biological processes that take place when we sleep, processes that have been fine-tuned over centuries to promote our health and survival. I learned to see sleep as an effective deep cleansing system that dramatically impacts every aspect of our lives, awake or otherwise. A system that increases memory formation and storage, deepens creativity, strengthens decision-making capabilities, bolsters the immune system and maintains emotional and mental health every single night. I dedicated a week to developing better sleep practices and implementing the start of a sleep schedule: going to bed earlier and at the same time every evening, staying away from screens an hour before bed, engaging in relaxing activities instead, such as reading or listening to music, napping for an hour after lunch (studies show that siestas can promote good health when taken in conjunction with a full night’s sleep). At the end of the week, I woke up and for the first time in my adult life and felt truly awake. In the past, I had often joked with friends about turning 30 and the general feeling of constant tiredness that I assumed was a ‘natural’ requisite to getting older. But when I woke up at the end of that week, not craving an extra hour in bed but feeling alert and energised, I realised that I had spent the last few years exhausted, both physically and spiritually, and I had been too distracted to realise.

In an online yoga session this week, the instructor briefly mentioned the idea of having the courage to rest and I reflected on what an important message that is right now for us all. It takes courage to prioritise rest in a society that glamourises overworking, makes us feel guilty for taking time off and expects us to be constantly connected. It takes courage to prioritise rest in a society obsessed with entrepreneurship—a society that confuses exhaustion with success, when what exhaustion really is, is a lack of balance in one’s life and the neglecting of one’s needs. Of course, there are cases where exhaustion is harder to avoid, for example for new parents or those who need to work multiple/night shifts. What is needed is a cultural shift which encourages and provides support in seeking more creative ways for different people to rest. With the events of last year in mind, particularly the heaviness of the Covid-19 pandemic and the exhaustion so many face in the ongoing battle against racism and inequality, we must develop a better relationship with sleep, perhaps now more than ever. To revel in sleep’s ability to provide both care and healing—physically, emotionally, mentally. To reclaim the right to a full night of sleep, without stigma or embarrassment. To find a renewed courage to rest.

Follow @elvira.vedelago

We've got great things to share!

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

and we'll keep you updated.

You can unsubscribe at any time

Terms & Privacy